Confront the Past, Change the Future

“Be vigilant,” I say to my son as I struggle to find words to express my concern. It is February 2020 and he is a high school senior, preparing to leave for Rome with his Latin class.

The world is reeling from the discovery of a highly infectious virus that is spreading around the globe, but my concerns extend beyond my son’s ability to resist a virus. Already we are witnessing racialized profiling of the disease: the “Chinese Virus,” the “Kung Flu.”

My son looks at me and says, “Um, Mom? I’m a U.S. citizen, born and raised in San Francisco!”

I recall the day 30 years ago when my grandfather struggled to find words to share with me as I headed to college in Los Angeles.

“Work hard for your education,” he said. “Hold your words close. Don’t be loud.”

I realized much later that my grandfather was expressing his hope and fear for me in America. He was saying, “Don’t miss the opportunity, but don’t be conspicuous.”

My story is not uncommon among immigrant families. It echoes the stories of many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States. My grandfather, in search of better opportunities for his grandchildren after my father’s death, led my family’s immigration in the 1970s from Taiwan to a small town in Pennsylvania.

Like many immigrants without education and language fluency, my grandfather, my mother, my aunts and uncles all took low-wage jobs to support their families. Their children and grandchildren went to college, and this was their American Dream. I was the first granddaughter to pursue a college degree.

Exiled from his homeland of China after World War II, my grandfather shared with me a profound sense of diaspora and unwavering hope. He also shared his fear.

My son learned fear firsthand when he was pulled into a separate line at a German airport for an intense search and interrogation by customs, days before the world shut down due to the surge of COVID-19 cases. He was the only student of East Asian ancestry in his school group, and the only one to be interrogated.

I reflect on my son’s experience as I commence the deanship during a moment of many national and international crises. What is the way forward?

A History of Discrimination

If we want to move forward, it helps to look back. Anti-Asian violence rose exponentially in 2020. History shows that during crises, Asian Americans, like other communities of color, bear the blame for economic, social, and political problems. Too often seen as the forever foreigner or the model minority, Asian Americans are sometimes portrayed as monolithic, dangerous, and un-American.

And although they are part of U.S. history, Asian Americans have lived and continue to live on the margins."

Chinese immigrants who built the transcontinental railroad in the 1880s and Filipino migrant farmworkers in the early 20th century were portrayed as job stealers. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first race-based anti-immigration act, and it remained in effect until 1952.

During World War II, people of Japanese ancestry — two-thirds of them American citizens — were “interned” in concentration camps here in the United States. After the Vietnam War, Southeast Asian refugees faced discrimination and violence. Following 9/11, South Asian communities in the U.S. experienced a surge in hate crimes.

I felt the weight of my grandfather’s hope and fear when I was growing up, one of the few Asian students in my middle school in Pennsylvania. It wasn’t until college that I began to identify as being Asian and being American.

And although they are part of U.S. history, Asian Americans have lived and continue to live on the margins.

I have heard plenty of discriminatory remarks by well-meaning people. “I don’t hear your accent anymore.” “I don’t think of you as Asian when I talk to you; your English is so good.” “You teach English literature, not Chinese?”

I wonder how long it will take until I am not a stranger.

The Answer is Among Us

Education is the way forward. With it, we can understand anti-Asian violence. Education is what we do at USF.

Educating all students about Asian Americans is the first step to stop anti-Asian racism. And one way to do that is to increase diversity of our faculty. Over the past two decades, the university has hired 28 predoctoral fellows, all ethnically diverse, who teach and provide mentorship for students.

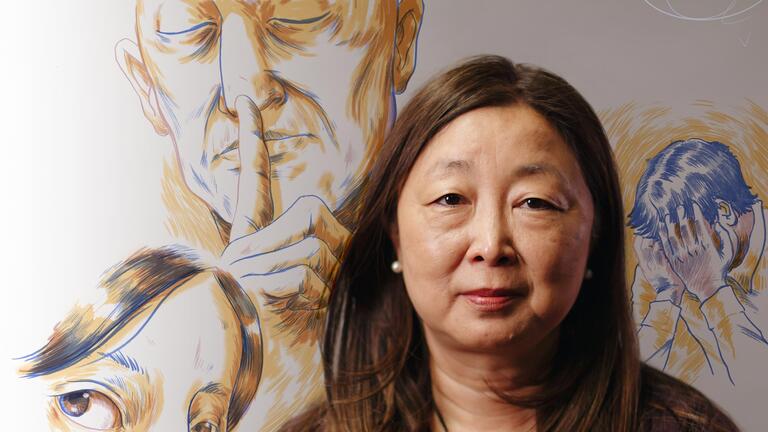

I was one of the fellows recruited in 1997 to teach medieval English and Asian American literature. Along with the other Asian American fellows-turned-professors, I helped to launch the Asian American studies program in 2000. It joins a curriculum that today includes African American Studies, Chicano/a American Studies, Gender and Sexualities Studies, and Critical Diversity Studies.

As we position faculty to serve as role models for Asian and Asian American students, we help students who are struggling. And we support Asians and Asian Americans as leaders in a world that pushes them into negative stereotypes.

Can We Do More?

I came to USF believing in the power of a Jesuit liberal arts education. I still believe.

At USF, we grieve anti-Asian violence. We ask our students where, how, and why racism exists. We believe that a Jesuit education empowers our students and prepares them to confront the injustices in the world and search for solutions. As interim dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, I believe that the future of USF is to strengthen our commitment to justice as the core of a liberal arts curriculum.

It is now summer 2021 and my son will leave for college in September.

“Be vigilant,” I say again, struggling with my words.

I remember my grandfather’s caution, but I see the world differently now.

“Work hard for your education, but let your words fly. Your voice matters,” I tell him.

I say the same to USF students: “Your voices are worth hearing.” It is my privilege to hear.

And it’s what our society needs to hear, if we are to confront the deep and historical ways we have harmed each other and move toward a world where every person and community in our society and the world thrive.