From Climate Change in Taiwan to the History of Tuberculosis in China: Scholars Share Their Research

On Saturday, February 6, 2016, members of the Chinese Studies Research Group (San Francisco Bay Area) welcomed two presentations about the latest research in the fields of ecocriticism and the history medicine. The group’s meetings, organized and hosted by the USF Center for Asia Pacific Studies, bring together scholars and graduate students from across the Bay Area to share their research in progress on topics in the humanities and social sciences, to network and create a sense of community in the field of Chinese Studies.

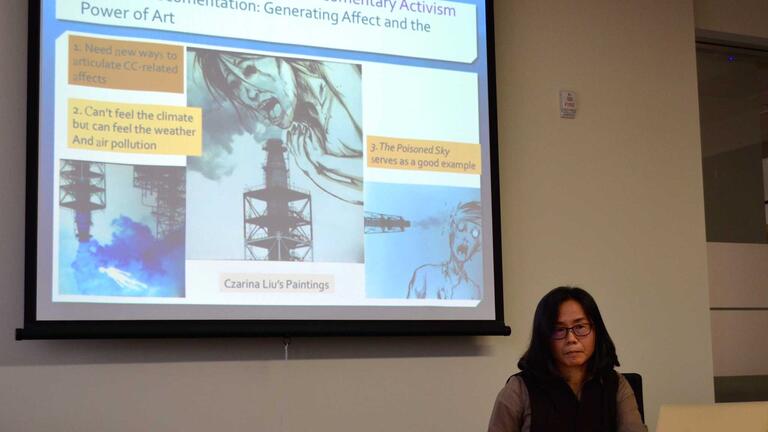

Scholars at the meeting had the opportunity to meet the Center’s new Kiriyama Professor for Asia Pacific Studies (spring 2016), Chia-ju Chang (張嘉如) (Associate Professor of Chinese, Modern Languages and Literatures, Brooklyn College-the City College of New York) and to hear about her research in the fields of ecocriticism and eco-cinecriticism. Through a variety of film and documentary clips, especially from Scott Chi’s The Poisoned Sky, an environmental protest film against the construction of a coal-burning power plant in Changhua County, Chang presented her work on climate change and cinema in Taiwan. Chang’s research project examines how art related to climate change and global warming should be addressed. Chang’s research shows that rather than relying on the typical tropes of spectacular, shocking catastrophic images of climate change, images which often cause viewers to experience "climate fatigue," the use of "micro-shock" to represent slow violence or shifting the focus to daily life struggles such as air/soil/river pollution are more effective in getting people interested or concerned enough to affect change. Prof. Chang will be continuing to work on this research while she is in residence at USF this semester.

Scholars at the meeting also learned about the latest research in Chinese medical history from Peiting C. Li, Doctoral Candidate, Department of History, UC Berkeley. Li presented her research in progress on tuberculosis treatments and the assertion of professional authority in Shanghai medical journal writing, 1920-1940. Tuberculosis, prevalent among workers in “dusty trades” (textile mills, pottery factories, etc.) and inhabitants of crowded living conditions (framed as traditional Chinese family living), was a widespread problem in China. After the discovery of the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882 and before the development of effective drug treatment in 1944, Li finds that patients had a wide range of therapies to choose from as there was no monopoly on treatment at the time. Examining medical writings published by Western-trained Chinese physicians, pharmaceutical companies, and proponents of Chinese medicine, Li analyzed these attempts to assert authority as producers of medical knowledge. Criticism of profit-driven drug companies, praise for drugs that would destroy the bacterial causal agent of tuberculosis, and promotion of diet therapy to cure symptoms illustrate the tensions between professional, commercial, public, and private interests at work in Republican Shanghai's medical information market. Li’s tuberculosis research is part of her dissertation on knowledge production and pharmaceutical medicine in Shanghai.