USF Pledges to Practice Greener Chemistry

Chemistry professors at USF have signed the Green Chemistry Commitment, a voluntary effort to reduce chemical products and processes that use or generate hazardous substances.

“It’s a formal pledge to bring sustainability to chemistry and to the teaching of chemistry,” said Jennifer Tripp, assistant professor of chemistry. As of this month, chemistry faculty at 240 universities — including Brown, Harvey Mudd, McGill, Northeastern, Technische Universität Berlin, and USF — have signed the commitment.

Green chemistry is sustainability at the molecular level, Tripp said. “The whole idea is that it’s better to prevent waste and reduce hazards rather than dealing with them later.”

Tripp said the Green Chemistry Commitment is a response to more than 100 years of “ungreen” chemistry.

“In the 1920s, chemists first used chlorofluorocarbons in electric refrigerators to keep fresh foods from spoiling, but it turns out that CFCs deplete the ozone layer,” Tripp said. “Then in the 1990s, chemists replaced CFCs with hydrofluorocarbons, but HFCs are greenhouse gases that warm the climate. So now green chemists are working on greener refrigerants” including propane and isobutane.

In keeping with the Green Chemistry Commitment, USF is removing hazardous solvents and reagents in all teaching and research labs, integrating principles of green chemistry and environmental justice across the chemistry curriculum, and sharing green ideas with colleagues in related departments such as engineering, environmental science, and biology, Tripp said.

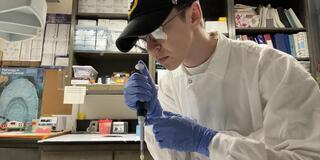

Kat McIntyre MS ’26, a graduate student in chemistry who earned a BA in chemistry at USF in 2024, said she has witnessed USF’s shift to greener chemistry.

“In my senior year when I was a teaching assistant for organic chemistry with Dr. Tripp, if she found a hazardous solvent in the lab, she replaced it with a less hazardous solvent. Or she’d say, ‘This solvent's properties and potential hazards aren’t fully known yet. Let’s be careful with it.’ Or she’d ask students, ‘What can we do in this lab to be less wasteful or more environmentally friendly?’”

Tripp said that USF’s green chemistry pledge aligns with USF’s Jesuit values. “It’s a public declaration of what we’ve been doing, in private, for years: caring for the planet and working to serve the common good.”

When they care for the planet and serve the common good, green chemists gain an edge in the job market, McIntyre said.

“In both industry and academia, employers are looking for people who can not only do chemistry, but can you make this medicine safer for patients? Can you make this product safer for consumers? Can you make it more affordable? More sustainable? Make it so we don’t get sued? Make it less expensive to produce so that we don’t lose our research funding?”