Shake the Status Quo

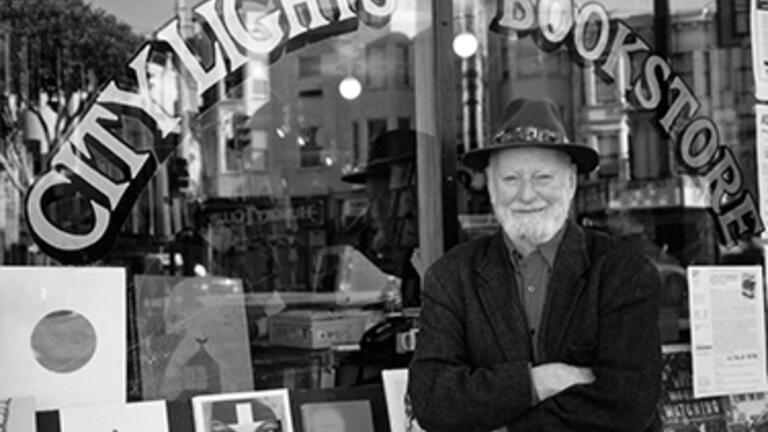

The Bay Area lost one of its strongest voices for social equity in the arts when Lawrence Ferlinghetti — author, publisher, and cofounder of City Lights bookshop in San Francisco — died this year at the age of 101.

For more than 60 years Ferlinghetti championed writers outside the mainstream. He published their work. He invited them to read at City Lights. He encouraged and befriended them. And in 2012 he inspired the Lawrence Ferlinghetti Poetry Fellowship at the University of San Francisco.

That fellowship, in turn, inspired me.

I was selected as the second-ever Ferlinghetti Fellow in 2015. That fellowship gave me a full ride to USF’s Master of Fine Arts in Writing program, and it opened a door to me and to others like me — people to whom the doors of higher education had long been shut.

My introduction to poetry wasn’t in books. It was in the world — doing graffiti and freestyling rap lyrics in the South Bay where I grew up, a first-generation Mexican American. When I was a teen, reading the words of old white men was far from anything I’d do. I was more likely to cut class and play video games. Then, when I was in community college, after years of academic floundering, my younger sister handed me a book called Poetry as Insurgent Art. The author: Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

In reading Ferlinghetti’s work, I started to believe that maybe a voice like mine deserved to be inside of books, too. I learned that Ferlinghetti was a weird Bay Area poet — like me — and the more books of his that I read, including A Coney Island of the Mind and Starting from San Francisco, the more I realized that poetry wasn’t beyond me. I learned, while wandering in City Lights and reading the poetry of Martín Espada, June Jordan, and Sonia Sanchez, among others whom I’d discovered on the shelves, that poetry could be about the dirty underwear in your lived-in apartment, about the neighborhoods we inhabit, about foreign landscapes and the ravages of warfare, about declaring yourself in a society that was designed to silence you.

“The only way poets can change the world is to raise the consciousness of the general populace,” Ferlinghetti wrote. It’s something that sparked a flame in me and others like me — to be voices, not only for ourselves, but for each other.

As it happens, Ferlinghetti taught at USF back in the 1950s, but not for long. “I was giving a lecture on the homosexual interpretation of Shakespeare’s sonnets and in walked the priest who headed the department,” he told an interviewer. “That was the end of my academic career.”

Today, USF is more open. I am proof of that. When, after years of having been rejected from other institutions, I found out I’d received full tuition as a Lawrence Ferlinghetti Poetry Fellow, I knew that poetry wasn’t just something to be written but to be lived, and it wasn’t just something for other people but for me.

I Am Waiting

I am waiting for my case to come up

and I am waiting

for a rebirth of wonder

and I am waiting

for someone to really discover America

and wail

and I am waiting

for the discovery

of a new symbolic western frontier

and I am waiting

for the American Eagle

to really spread its wings

and straighten up and fly right

—Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Excerpt from “I Am Waiting” from A Coney Island of the Mind. Copyright © 1958 by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Reprinted with the permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation.

Alan Chazaro is a Bay Area writer and teacher. His books, This Is Not a Frank Ocean Cover Album and Piñata Theory, are available through Black Lawrence Press. This essay was adapted, with permission, from an essay published in the San Francisco Chronicle.