The Man Behind the Camera

On Feb. 19, 1945, Joe Rosenthal waded ashore with a battalion of Marines in the attack on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima. Instead of a rifle, he carried a camera above his head.

The sea was choppy, and it was hard running in the sand, he recalled. Gunfire and grenades pelted the beach. Two Marines were hit and dropped dead next to him and another ran past him.

“It was like walking through the rain and not getting wet,” Rosenthal said later, describing the battle scene. “No man who survived that beach can tell you how he did it.”

Rosenthal was a long way from San Francisco and USF, where he was a student until 1943. Like so many others, he left the university hoping to become a soldier after the U.S. entered World War II. But he was turned away because of poor eyesight.

Instead, he did a short stint with the United States Maritime Service before becoming a war photographer for the Associated Press. He had some experience, having worked as a photographer for the AP while he was a USF student.

Four days after landing on Iwo Jima, Rosenthal took a photo of six Marines raising a large American flag at the top of Mount Suribachi, marking the United States’ takeover of the island.

The photo went on to be one of the most famous images in history. Next year, 2025, marks the 80th anniversary of the battle of Iwo Jima and Rosenthal’s photo.

On Feb. 23, 1945, Rosenthal captured the image of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima in 1/400th of a second, later describing the experience as “largely accidental.” The 5-foot 5-inch photographer had to stand on a pile of stones to see the flag raising. Then, others walked in front of him as he prepared to take the shot. As the flag went up, he swung his bulky Speed Graphic camera toward it.

“That is how the picture was taken, and when you take a picture like that, you don’t come away saying you got a great shot. You don’t know,” Rosenthal wrote in a 1955 first-person account in Collier’s magazine. Rosenthal died at age 94 in 2006.

It was like walking through the rain and not getting wet…No man who survived that beach can tell you how he did it.”

Joe Rosenthal ’43

The photo was important because the battle for Iwo Jima and its two airfields was key to American success in the Pacific. In the end, the conflict took a massive toll, with 26,821 Americans wounded or killed and 22,000 Japanese killed.

After taking the flag-raising photo, Rosenthal made his way back down Mount Suribachi to the shoreline. There, he took a transport boat out to the command ship, where he wrote captions for his photos and sent them with the undeveloped film by seaplane to Guam.

Four days later the flag-raising photo was transmitted worldwide by the AP. It was published on the front pages of more than 200 newspapers in the U.S.

The photo came at a time when America was struggling in the war, says Tom Graves, a retired photographer in San Francisco who knew Rosenthal through their membership in the U.S. Marine Corps Combat Correspondents Association. In the first days of Iwo Jima, there were thousands of casualties and the news caused worries at home.

“We thought we would win the war, and we were losing,” Graves says. “When Joe’s photo came out five days into the battle, people saw the raising of the flag as a sign of victory. The doom and gloom started to lift.”

Rosenthal didn’t see the photo for another five days until he arrived on Guam. He was congratulated for the photo, but initially there were questions.

Some questioned whether he staged the shot. He said he didn’t, and witnesses and the AP verified it was not staged. There were also questions about who was in the photo. No faces are visible, and the Marine Corps initially misidentified some of the subjects.

Still, when Rosenthal saw the photo, he saw why it had captured so much attention.

“I have thought often in these 10 years of the things that happened quite accidentally to give that picture its qualities,” Rosenthal said in the Collier’s article.

“The sky was overcast, but just enough sunlight fell from almost directly overhead, because it happened to be about noon, to give the figures a sculptural depth. The 20-foot pipe was heavy, which meant the men had to strain to get it up, imparting that feeling of action. The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.”

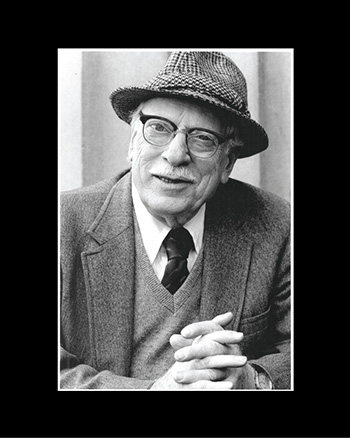

Photo provided by Anne Rosenthal.

At the time, the war effort was being paid for with war bonds, but they weren’t bringing in the amount expected. Graves said the flag-raising photo was used for the seventh war loan drive, and millions of posters were printed with the image. The effort raised $26 billion from war bond sales, helping to fund the end of World War II.

The photo also won a Pulitzer Prize and was printed on a first-class postage stamp. Rosenthal returned to San Francisco a hero. “I, who had never been asked for an autograph in my life, was now being asked to sign dozens of these pictures,” he recalled.

Anne Rosenthal says her father printed thousands of copies of the photo over the next six decades, mailing one to each person who asked for it. The original negative of the photo is in a locked vault in AP headquarters in New York City.

An art conservator living in Marin County, Anne Rosenthal recalls attending the 1954 dedication ceremony of the Marine Corps Memorial near Arlington National Cemetery, a 100-ton bronze sculpture depicting the scene in her father’s photo.

“Within the work he did, he did something very special,” she says. “To be known for that one moment — it eclipsed so much of his otherwise normal life.

Anne Rosenthal remembers her father playing classical music at home in San Francisco after the war. His bookshelves were filled with the classics, like Don Quixote. She says the Jesuits at USF had an impact on her father.

“Education was important to him. He would say it’s important to have a well-rounded education and to him that meant sciences, literature, music.”

Raised an Orthodox Jew in Washington, D.C., Joe Rosenthal converted to Catholicism around the time he was at USF, his daughter says.

When you take a picture like that, you don't come away saying you got a great shot. You don’t know.”

Joe Rosenthal ’43

Carl Nolte ’61 worked with Rosenthal at the San Francisco Chronicle, where the photographer was employed after the war for 35 years until he retired. Nolte was a reporter and often was sent on assignment with Rosenthal.

“At some point, he discovered that I had gone to USF, and we talked about it,” Nolte says. “He was interested in the liberal arts.”

Rosenthal didn’t return to USF; he had responsibilities at the Chronicle and as a new husband and father. But he was proud of his school.

“Joe had his loyalties: one was to his family, one was to the Marine Corps, one was to his trade as a photographer, and one was to USF,” Nolte says.

Rosenthal was awarded the U.S. Navy Distinguished Public Service Award, as well as the Marine Corps Distinguished Public Service Award by the Marine Corps, for his war photography. With the 80th anniversary of the flag-raising photo, there is an effort, led by Graves, to get the U.S. Navy to name a ship after Rosenthal next year. So far, a petition to have a ship named for Rosenthal has nearly 7,000 names, as well as the support of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

“There are very few citizens who have had an effect on winning a war like Joe Rosenthal,” Graves says. “This will carry his name forward into the future.”

In San Francisco, there are also efforts to plan a Rosenthal photo exhibit next year at the San Francisco Historical Society. In 2022, the California State Library in Sacramento dedicated an exhibit to Rosenthal and his images.

A decade after he took the flag-raising photo, Rosenthal reflected on his experience — and on a photo he took on Iwo Jima of the Marines who died next to him as they stormed the beach.

“I will accept that the flag-raising shot, for which I can take only such a small part of the responsibility, is the best picture I have ever made,” Rosenthal said. “To me it is not alone a snapshot of five Marines and a naval medical corpsman raising the flag. It is the kids who took that island and got that flag there.”

To learn more about the effort to have a ship named for Rosenthal, visit ussjoe.org