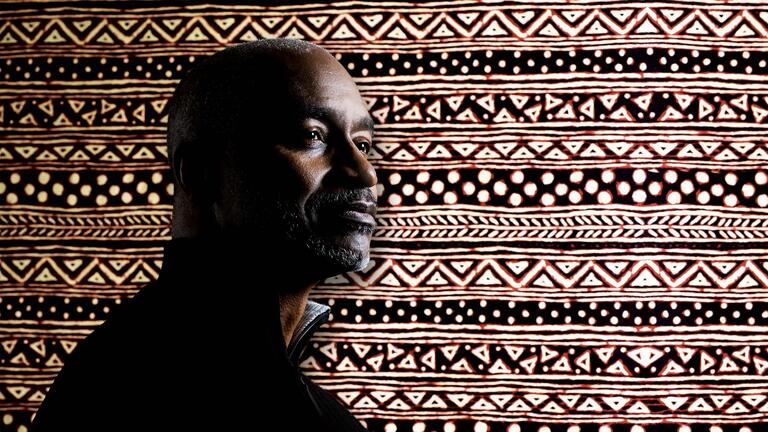

The Joe Marshall Plan

Joe Marshall founded the Omega Boys Club with the belief that many inner-city youth want to escape lives of drugs, gangs, and violence, but don’t know how. His no-nonsense, no-judgment program saves their lives.

Then it sends them to college.

Joe Marshall ’68 is live on the air at San Francisco’s KMEL radio station, asking questions, telling stories that don’t often get heard on a hip-hop station, and challenging his listeners to think.

Tonight’s topic is women, and Marshall is slamming the current rash of female-based reality shows, arguing that their catfight ethic is demeaning to women everywhere. “Why do people enjoy these reality shows and want to see women attacking each other?” he asks. “It disgusts me, it’s just not entertaining to me.”

The subject shifts quickly to Michelle Obama. Marshall calls her “a classy lady” and suggests that she’s the opposite of the female hip-hop and rap stars typically heard on the station.

“Has Michelle had an impact on the way young women act?” he asks the call-in audience. “I want to know what effect Michelle has or hasn’t had.”

This is the Street Soldiers weekly radio show. Every Sunday night since 1991, Marshall has used it to address violence, gangs, the black experience, life in the city, and just about anything else he, his co-hosts, and his listeners think is interesting or important.

Billed as a “solutions-oriented call-in show for youth,” the KMEL broadcast is also the voice of Alive & Free, a San Francisco youth organization that Marshall co-founded more than 28 years ago as the Omega Boys Club, an after-school program that gets youth off the streets and gives them skills to succeed in school—and life.

During the two-hour broadcast, Marshall improvises. He changes direction—and topics—in an instant. It’s a lot like jazz, Marshall says during a chat at Alive & Free’s headquarters in the city’s Dogpatch neighborhood. Playing jazz piano, he adds, is one of the few hobbies he has time for.

A Campus Radical

Marshall is an author, educator, community activist, police commissioner, winner of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, trustee emeritus of the USF Board of Trustees, and recipient of a USF honorary doctorate degree. Bill Clinton and Oprah Winfrey are among the many fans who celebrate his work.

He grew up in the tough South Central neighborhood in Los Angeles and came to USF from LA’s Loyola High School. “When I got up here, I found that just about the only other blacks were on the basketball team,” he says. “I loved Jesuit education, but I wanted a little more color in it.”

So Marshall became, in his own words, “the campus radical.” He founded a chapter of the Black Student Union (BSU), pushed for a black studies curriculum, and fought to bring more ethnic diversity to the university.

“I met Joe in my freshman year, when the handful of African American students gravitated together and ate lunch in the cafeteria,” says classmate Adrienne Riley, who’s on the board of Alive & Free. “He wanted to change USF then and he’s followed through.”

Marshall still remembers the day in 1970 when he thought his future was wrecked before it started. He had graduated from USF and was working on his teaching credential when a confrontation between the BSU and the administration resulted in hot words and broken windows.

I loved Jesuit education, but I wanted a little more color in it.”

Following a dispute after an intramural basketball game, Marshall and about 40 other BSU students took over a room in the student union. They barred the doors, broke some windows, and trashed the place, “essentially making a shambles of all the progress and good faith we had built up over the preceding years,” Marshall wrote in his 1996 best-seller, Street Soldier: One Man’s Struggle to Save a Generation—One Life at a Time.

The dean of men fingered Marshall as a ringleader and ordered him to appear at a university hearing, accusing him of destroying campus property and inciting a riot.

Marshall was 22 years old and student-teaching at San Francisco’s Woodrow Wilson High School. “I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to lose it all,’” he says. “I went in there with my rosary going and everything.”

USF law professor Robert Taggart spoke for Marshall at the disciplinary hearing. He described life for an African American student on a predominately white campus, the casual racism of some of the students, and Marshall’s fight to make changes he knew had to come.

The next day, the complaint was dismissed. It was more than a win for Marshall.

“Everything that happened at USF prepared me for what I would become in life,” he says. “It all began at USF. There was an awakening of my leadership ability, recognition that I could do things.

“The school’s new motto, ‘Change the World from Here,’ is exactly what I was doing.”

A’s in Math, F’s in Life

Marshall went to work teaching math in the city’s high schools and middle schools, always expecting the most from his students. “The only way to pass my class was to pass my tests,” he says. “I’d give them homework and call their homes. I figured if they could survive me, they’d be fine.”

The students nicknamed him Mean Mr. Marshall. Still, they felt his absolute commitment and clamored to get into his class.

But something happened after they left his middle-school classrooms for high school. “I’d find those kids on drugs, selling drugs, getting pregnant,” he says. “Worst of all, I found myself going to their funerals.”

Those experiences changed him.

“I realized that being a good teacher wasn’t enough,” Marshall says. “My students were getting A’s in math but F’s in life.”

He decided to do something about it. In 1987, Marshall co-founded the Omega Boys Club, to give youth an alternative to the streets and give their lives direction. Many were gang members, and the number-one goal was to keep them out of prison.

About 30 young people attended the first meeting, but half of them dropped out when they learned how much work was required. The 15 who showed up at the second meeting were enthusiastic, however, and at the third meeting they brought their friends. Since then, the club has never had to recruit kids. They just show up.

Marshall’s message was a simple one: If you stick with the program, you pick the college and I’ll find a way to get you there.

“The irony was I had no money. I had three kids of my own and needed to get them through school,” Marshall says. “But I had faith that if you do good things, good things will happen.”

I had faith that if you do good things, good things will happen."

It never should have worked, Marshall admits, but somehow it did. KGO-TV aired a five-part series on the club, followed by an on-air pitch from the station’s general manager, the late Russ Coughlan, to support the program. The money came in and is still coming.

Today, students who stay with the program and are accepted to college can apply for an Alive & Free scholarship worth up to $10,000 per year. They’re awarded based on several factors, including family need.

This year, the organization is celebrating its 200th college graduate. “And 50 of those 200 have graduate degrees,” Marshall says.

Believers Out of Doubters

Marshall believes youth violence is a disease, one that can be treated and prevented. His prescription is Alive & Free.

At its core is the Leadership Academy, which serves about 200 young people every year, ages 14 to 24. Expectations are high, class participation is mandatory, and success is the new norm.

These days, as many girls participate in the program as boys. The academy helps them develop the math, literacy, and critical-thinking skills necessary to graduate from high school or pass the GED exam, and it nurtures the inner strength they need to escape from the culture of violence that plagues so many of the city’s low-income neighborhoods. Special discussion groups help them vent a lifetime of anger and disappointment.

Many say this is the closest thing to a family they’ve ever had.

For the university-bound students, there are more classes, and more rigor, in a separate college-prep program that includes financial literacy classes, academic counseling, and help in applying to and selecting colleges. Alive & Free alumni continue to receive counseling and tutoring—long distance, if necessary—while they’re in college.

Marshall, with his tough-love attitude, has never made it easy for the thousands of young people who have passed through his program over the years. That’s the point.

“It’s a battle with the thug image,” Marshall says. “It’s a real tug-of-war between the streets and us.”

Not to mention the problem of convincing a teenager to give up one or two nights a week for classes when they could be spending that time with friends. The Leadership Academy meets Tuesday nights from 5:30 to as late as 10, and the three-hour college prep sessions are held on Thursdays.

“I didn’t want to come,” admits 25-year-old Dana Ward-Robinson, a graduate of Spelman College in Atlanta. “The night classes didn’t leave a lot of time for what I wanted to do in high school.”

But her years at the club helped focus her life and build a network of friends and gave her a feeling that anything is possible.

“The best part of Omega is that I learned to be mindful of my environment and the people I surround myself with,” she says. “I learned how I could be a better person. This is my family. And Dr. Marshall? He’s awesome.”

The best part of Omega is that I learned to be mindful of my environment and the people I surround myself with."

Ward-Robinson continues her studies while teaching at an after-school program. “I want to be a doctor,” she says before quickly catching herself. “No, I mean I will be a doctor.”

That kind of confidence is every bit as important to students’ future success as strong math and reading skills, Marshall says.

“The biggest block is often their friends, who tell them they can’t go to college or they can’t leave San Francisco,” he says. “It’s our job to make believers out of doubters.”

The More You Know, the More You Owe

Alive & Free’s success—along with his popular book—has given Marshall visibility not only in San Francisco but throughout the country. So when then-Mayor Gavin Newsom was looking to remake the city’s Police Commission, his first thought was Joe Marshall.

“I had seen firsthand the work he had done and knew what a presence he was in the community,” says Newsom, who is now California’s lieutenant governor. “I wanted someone on the commission who didn’t just understand law enforcement issues but the underlying problems. Joe was a different voice and offered a different and needed perspective.”

Marshall joined the commission in 2004, and Mayor Ed Lee reappointed him to his fourth term in 2014. Marshall says it’s one of the most rewarding jobs he’s ever had.

“At first, my attitude was that my community has enough problems and that what I needed to do was make sure the police didn’t make it any worse,” Marshall says. “But for me to have a community voice on the commission is priceless. I can get in the middle of tense relationships and move them forward.” Relationships between the police and the minority community have been getting better in recent years “but only because we work hard at it.”

Tony Ribera, former San Francisco police chief and head of USF’s International Institute of Criminal Justice Leadership, calls Marshall “a model of positive leadership” and says he “helped the police department grow into a 21st-century organization.”

It always comes back to USF, often in ways he never expected, Marshall admits.

On a 10-day trip to Israel with community leaders in 1994, Marshall met then-USF President John Schlegel, S.J., and the two hit it off. Later, when the university was looking for a new trustee, two former classmates already on the board recommended Marshall for the post: Adrienne Riley and Louis Giraudo, the board’s chairman.

“I was the last person I ever thought would be a university trustee,” Marshall says.

“We had to kind of convince him,” admits Riley.

Marshall left the board in 2006 after reaching the term limit, but he is still active on campus. He’s a regular on panels and seminars, has taught part-time in USF’s ethnic studies department, and serves on the advisory board of USF’s Upward Bound chapter, a college-preparatory program. He’s also a regular at Memorial Gymnasium, where he follows his beloved Dons. “If we ever get a really good team, we’ll own this town,” he says.

At a reunion of MacArthur Foundation grant winners, Marshall recalls looking around at the other high-powered recipients and wondering, “What the hell am I doing here? There are times when I just can’t believe it.”

It’s a momentary lapse. Only “I can” is acceptable at Alive & Free.

“Very few people have had such a profound effect on me as Joe Marshall has,” says USF diversity scholar Clarence Jones, who helped Martin Luther King Jr. write his “I Have a Dream” speech. “He’s like a lighthouse that’s pointing a beacon light. If you want to get through the storm, this is the course you must take.”

He’s like a lighthouse that’s pointing a beacon light. If you want to get through the storm, this is the course you must take.”

More than two dozen cities in the United States are on that course and have adopted the Alive & Free model for their communities. It has even spread internationally, establishing programs in South Africa, Thailand, and Canada.

“He’s changed lives and saved lives,” says Riley. “This isn’t [just] a job for Joe, it’s his life.”

It’s a life Marshall is dedicating to changing the world, one kid at a time.

“Like my grandmother said, ‘The more you know, the more you owe,’” Marshall recalls, leaning back in his chair in his classroom-turned-office. “It’s been a great, wonderful, joyous ride, but I got a lot more to do.”