Ambos Nogales

Ambos Nogales — a city bisected.

Crossing from one part of the city to the other, we approach border security kiosks and are shunted. Like cattle, one of my companions suggests.

The sun shines through the slats and stripes our clothing and skin. The shadows imprint a pattern.

It is impossible to ignore the bars and barbed wire, which deliver a message: I need protection or something needs protection from me.

We have arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border. At the wall that holds our national attention.

Along with a dozen other Master in Migration Studies students, I am part of a USF-led immersion to a city half in Arizona and half in Sonora, Mexico.

Our hope is to better understand the migrant experience and borderland issues.

Immersion means being on location and in conversation with people, engaging with how they think and responding to their circumstances.

My class spent weeks reading immigration policy and theory, and tracking the media’s coverage of President Donald Trump’s efforts to expand the nearly 700 miles of existing wall.

The weeklong trip is a chance to introduce a physical reality to my research about human migration and empathy.

I’ve been to Mexico before. As a tourist, as a photojournalist, as a volunteer.

But this is a chance to explore an issue — to converse and share meals with people whose lives are connected to the wall.

Over several days, our host — the Jesuit nonprofit Kino Border Initiative (KBI), which works to facilitate humane, just, workable migration — connects us with borderland people, first in Mexico and then the U.S. We meet people with divergent perspectives on immigration.

As students at a Jesuit university, we are encouraged to weigh what we see against the idea of cura personalis: care for the whole person.

The community responses to the border show up on the wall itself in the form of spraypaint and handiwork and mementos.

The wall is a place of prayer and protest, of hands and objects passed through to loved ones.

On one of our first days, we hike a wall-less section of trail that migrants take for the border crossing.

It is one thing to read about the heat and thirst of a desert crossing, but being a vulnerable and thirsty body, even briefly, is a revelation.

We carry water, are well rested, have recently eaten, and know we’ll have shelter for the night, unlike the people whose path we walk.

Along the trail lie photos, letters, maps, and water bottles — discarded in haste or because the difficulty of the journey demands it.

When you are new to a place, there is always a question of how to be helpful, how to connect.

At a comedor, a community center run by KBI in Nogales, Mexico, the question is answered when we’re thrown into making and sharing a breakfast of beans, tortillas, sausages, and greens.

I worry that making photographs might be a barrier to connecting.

Instead, my camera is a conversation starter. People are eager to show me photographs of their own, or to ask about my gear and what I do.

One man shows me a photo of his daughter in the U.S. After living in the Pacific Northwest for 15 years, he was deported before her birth.

His baby is the reason he will continue to attempt the crossing, he explains.

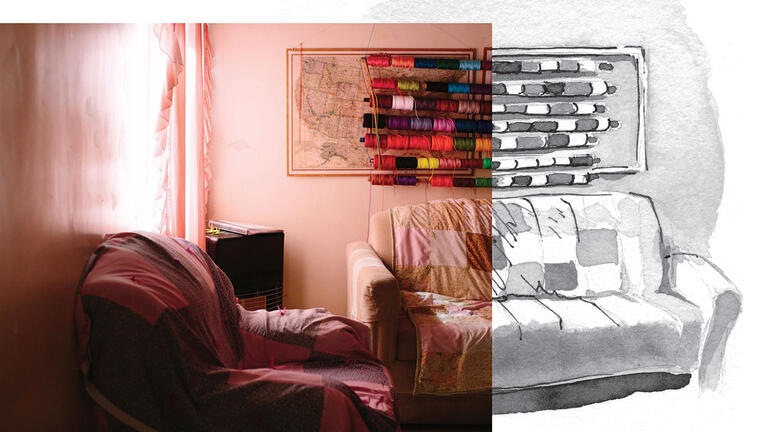

On another day we visit a women’s shelter and speak with two survivors of physical abuse.

They fill their days with essential tasks and tell us that cooking and making jewelry and playing board games together is a comfort after what they’ve been through.

For the second half of the trip, we cross to the U.S., en route to speak with those the wall impacts on the other side of the border. We carry our passports. We are anxious.

What questions will we be asked by border security? Will it take longer for those with Latino surnames to be green-lit for the crossing?

Once across, we drive to Tucson, Arizona to a court where hearings take place in accordance with Operation Streamline, a U.S. initiative that allows for the prosecution of up to 70 people at a time for crossing illegally.

Many we see in court were apprehended on the trail we walked.

Our class takes a trip to the town of Arivaca to ask ranchers how living at the border shapes their lives.

Some leave water out for migrants passing through. Some find bodies. Some say more border security is needed to halt or slow the crossing.

In Arivaca, it seems like every third car is marked “Border Patrol.”

I’m curious about the response of other locals to living in a community where apprehension, detention, and deportation are visible and frequent. I notice “No More Deaths” signs, and spend the afternoon hunting instances of work by Tucson muralist Joe Pagac.

I’m taken by the exuberant, vivid works Pagac paints of borderland residents, and how they counterbalance the steel and barbs of border architecture.

I make a pilgrimage alone to St. Xavier, a nearby mission known as the White Dove of the Desert. It was founded in 1783 by Fr. Eusebio Kino, for whom KBI is named.

I am a U.S. citizen in a church built by Spaniards on Native American land that was once part of Mexico.

I’m struck by the way fresh perspectives make new understandings possible. I consider the borders we attempt to cross daily — and the courage required for the crossing.

If you’ve been on a USF immersion, we’d love to hear about it. Email us at usfnews@usfca.edu and tag us on social #USFCAalumni

Immersions at USF

Discover, connect, serve, reflect

"A USF immersion trip is about learning, serving, and falling in love with the world. Traveling in places such as Mexico, Borneo, and Appalachia, students meet people who open their eyes — and often change their lives. In many immersions, students learn about injustice. They connect with people in vulnerable communities, cultivate empathy, and grapple with privilege, in the Jesuit tradition. About 550 students participate each year." – Luis Enrique Bazan, associate director for immersions

- Appalachia, West Virginia

- Borneo, Malaysia

- Bilbao, Spain and London, England

- Cali, Colombia

- Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- León, Nicaragua

- Lima, Peru

- Puebla, Mexico

- Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Rome, Italy

- Salzburg, Austria

- Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

- South Africa

- Tenderloin, San Francisco

Find out more about immersions at myusf.usfca.edu/immersions