Bold Beyond

If you could build your dream home in the heart of San Francisco, what would it look like?

That’s the pitch that persuaded Jeremy Kasdin to leave Princeton University and lead USF’s engineering program.

Starting fresh, USF is planning a home for engineering that avoids the pitfalls of institutions too entrenched to stretch in new and needed directions, Kasdin says. “We’re creating a new engineering program to educate a new kind of engineer — a liberal arts engineer steeped in Jesuit values.”

The engineering program isn’t USF’s only new undertaking. By 2022, the university aims to raise $100 million to fund an array of fresh academic initiatives and student programs, including the recently launched Black Achievement Success and Engagement (BASE) program and the new Honors College.

These three initiatives will attract top students and faculty, tackle systemic race and gender disparities in higher education and the workforce, and embody USF’s mission to educate the whole person and change the world for the better.

Engineering the Future

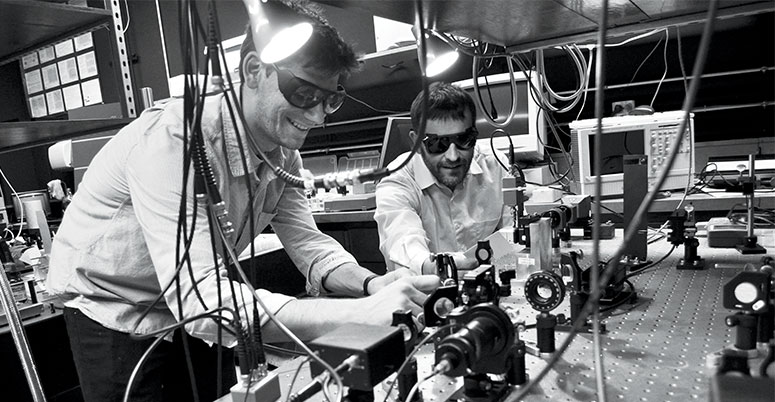

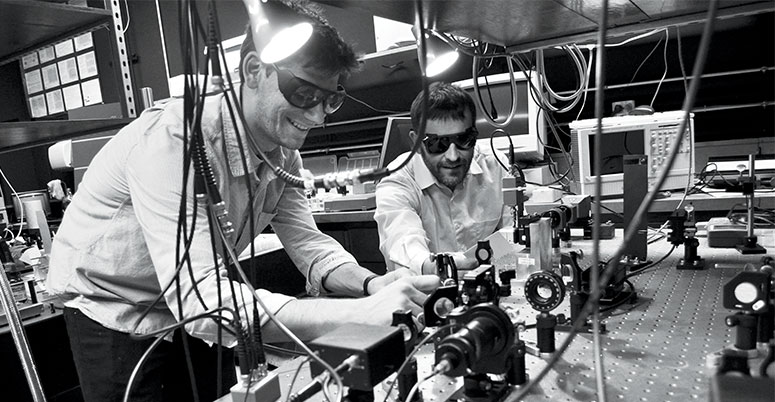

The engineering program, known as Engineering at USF and expected to launch in fall 2020, will combine foundational skills in math and science with the rigor of a Jesuit liberal arts education.

At most engineering schools, students focus narrowly on math and science, says Associate Dean Chris Brooks, who has led curriculum development for the new program.

“Students at other schools take philosophy and history and writing, but those are seen as things to check off and not think about too much,” Brooks says. “But industry leaders will tell you, ‘I really need people who can write, people who can work on a team and lead a team, people who understand the big picture and can ask those why questions.’ Those are all Jesuit liberal arts questions.”

To give students that well-rounded education, USF is taking a project-based approach to learning from the very beginning — unlike a more traditional approach to engineering where students typically don’t get hands-on experience with projects until their senior year. That may mean that USF engineering students early in their education won’t have all the technical skills they need, Brooks says, but they’ll learn what they need when they need it.

Say, for example, students want to monitor groundwater pollution at a farm. They’ll need to know a bit of programming, maybe how to build a sensor, and some chemistry. They can learn those skills in the context of the project, Brooks says.

For most students, learning by doing is more effective (and engaging) than learning by lecture, Brooks says. Also, project-based learning helps students connect abstract knowledge to real problems and gives them a chance to integrate different types of knowledge from other courses.

Meanwhile, the program aims to challenge the very notion of who a typical engineer is. Nationwide, just 21 percent of bachelor’s degrees in engineering were earned by women in 2017 and less than 15 percent of engineering bachelor’s degrees were earned by African American and Latino students, according to the American Society for Engineering Education.

USF, by contrast, wants its engineering students to reflect the university’s broader student body: at least half women, ethnically diverse, and more than a third of whom are the first in their families to attend college.

The program will offer scholarships to reach more students, recruit women and people of color working in engineering to serve as mentors, create pathways to internships, and ensure that its faculty reflects its student demographics. Incoming first-year students will arrive on campus before classes begin to brush up on any needed math and technical skills, to build community, and to learn the ins and outs of attending college, particularly important for students who are the first in their families to do so.

“As for specific concentrations within the program, our initial plan is to have a sustainable environmental engineering program, a sustainable built environment concentration, and an electrical and computer engineering program that will complement the current physics and computer science majors,” Kasdin says.

USF’s approach is the future of engineering education, Brooks says. Not only has much been written about the need for diversity within engineering, but the National Academy of Engineering has long advocated for a more holistic approach to engineering that encourages students to learn across engineering specialties and incorporate knowledge from other fields.

Few universities have taken up the call to restructure their more traditional, segmented approaches in which students focus almost exclusively on acquiring standardized technical knowledge for a particular engineering specialty, Kasdin says.

By adding an engineering program, USF is recognizing that a broad liberal arts education must now include engineering, both for those students who want to major in it and also for students of all fields who need to understand the way engineering affects their lives."

Righting Past Wrongs

Just as USF’s engineering program will support its diverse student population, so too is the university working to support students of all backgrounds, such as first-year media studies student Julian Sorapuru ’22.

In coming to USF from New Orleans, where African Americans make up more than 60 percent of the population, Sorapuru knew he’d be among the minority — African American students made up 5.4 percent of the student population in fall 2017. But he was intrigued by the university’s BASE program, which aims to make black students feel more valued, included, and encouraged to reach their academic potential — all with a goal of increasing representation of black students on campus.

‘I knew BASE was something I wanted to be part of,’ says Sorapuru of the program, which just completed its first year. ‘It’s great to be surrounded by all these black people who are driven like me, who have an interest in social justice, and who build a great sense of community together.’"

Sorapuru’s experiences are backed up by extensive research into effective educational practices for minority students, says Candice Harrison, BASE faculty director and associate professor of history. She said research has shown that black students in particular need to be surrounded by other people who look like them, including peers, faculty, and staff. With those connections, she says, black students go on to excel at higher rates than they do without that experience.

Thoroughly understanding black students was a key component in creating BASE. Instead of simply putting a bandage on concerns about black students’ experiences at USF — African American students often report feeling isolated at USF and graduate at a lower rate than others do — the university created a comprehensive program that supports and inspires black-identified students across three areas.

In the Black Living-Learning Community, first-year and sophomore students live together while exploring black history and engaging with the local black community. The students take two courses together throughout the year, including a new African American Studies course that teaches them about black activists and introduces them to black faculty from around the university who give guest lectures.

In the Black Scholars program, high-achieving black students receive four-year scholarships that are up for annual renewal and specialized honors coursework — along with internship, mentorship, research, and service opportunities — that prepare them to serve the needs of underserved communities through their chosen careers.

The Black Resource Center supports all of USF’s black students, including those not reached through the black Living-Learning Community and Black Scholars. Newly opened at Gleeson Library/Geschke Center, the resource center serves as a formal and informal meeting space for black students, hosts workshops on a wide number of topics such as mental health and wellness and financial planning and literacy, and serves as a one-stop resource for guiding black students through USF.

“As an institution, we are absolutely committed to serving marginalized people,” Harrison says. “For me, BASE is very much about living out our Jesuit mission. I want our black students to feel as though they’ve graduated because of USF — because they got all the support, all the resources, all the mentoring that they needed to be successful.”

Preparing Tomorrow’s Leaders

Another program designed to set students up for success is USF’s newly launched Honors College, established with a $15 million gift from philanthropist and classical music composer Gordon Getty ’56. It offers a 30-unit curriculum for the university’s top students.

At first glance, last spring’s Honors College course called Gun Violence, Music, and Youth brings together two unlikely instructors: a composer from the Performing Arts and Social Justice program and a public health scholar from the School of Nursing and Health Professions. But dig a little deeper and you’ll discover a class that encourages Honors College students to look at how gun violence, ultimately a public health issue, can be viewed and addressed through music.

Guiding students toward making such connections across disciplines is a hallmark of the Honors College. “We gather top students from every discipline and put them to work on real-world problems,” says Christine Young, Honors College director and associate professor of theater. “This is the first college of its kind at a Jesuit university — absolutely we’re out to change the world.”

The college, which enrolled its first 160 students last fall, offers small, seminar-style courses in which students can learn from their peers and professors and dig deep into different subjects. The goal, says Young, is to give these students the tools they need to become leaders in whatever fields they pursue.

The Honors College is not just about having courses that have a larger reading load or more difficult assignments, Young says. It’s about depth and breadth. As with the engineering program, it’s meant to be cross-disciplinary and offer students a full Jesuit liberal arts education.

“One of the big complaints that comes out of different industries today is that students are often educated in a way that siloes their knowledge — this knowledge belongs here, this knowledge belongs there,” she says. “As we face global problems like climate change and poverty, people are coming to understand that the more diverse the group that works on a problem, the better, because different people bring different strengths and different viewpoints, and the more they’re able to draw knowledge from multiple sources, the more likely they are to solve those problems.”

Megan Schneider, a psychology major in the Honors College, describes her Rethinking Islam class as “one of the most impactful classes I’ve taken at USF so far.” The course challenged her to analyze different writings and to examine the biases of each writer, the historical context of the writings, and the credibility of the sources. She sees the benefits of such skills, no matter the field.

I feel like the Honors College gives me a leg up, in that I’m able to examine content and contribute holistically instead of just looking at something through one lens."