Compassion in Action

Laura Sabin ’10 sat with her patient. She asked gentle but probing questions, as she’d been trained.

What’s going on in your life now? Why does it feel bad when we ask you to have a mammogram?

The patient, who suffered from HIV/AIDS and congenital heart disease, was refusing a mammogram check for breast cancer — even though a doctor had felt a lump in her breast.

She was tired of bad news, she told Sabin.

Pressing further, Sabin learned the woman’s mother had died of breast cancer and that she was homeless, in her 50s, and had left her abusive husband. She didn’t have family or close friends to accompany her to the exam.

“How about if I go with you?” asked Sabin, who at the time was a recent USF nursing graduate interning at the nation’s first HIV/AIDS clinic, Ward 86, an outpatient facility at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

The patient glanced at her warily, unsure. Sabin’s look was sincere. The patient softened. That would be okay.

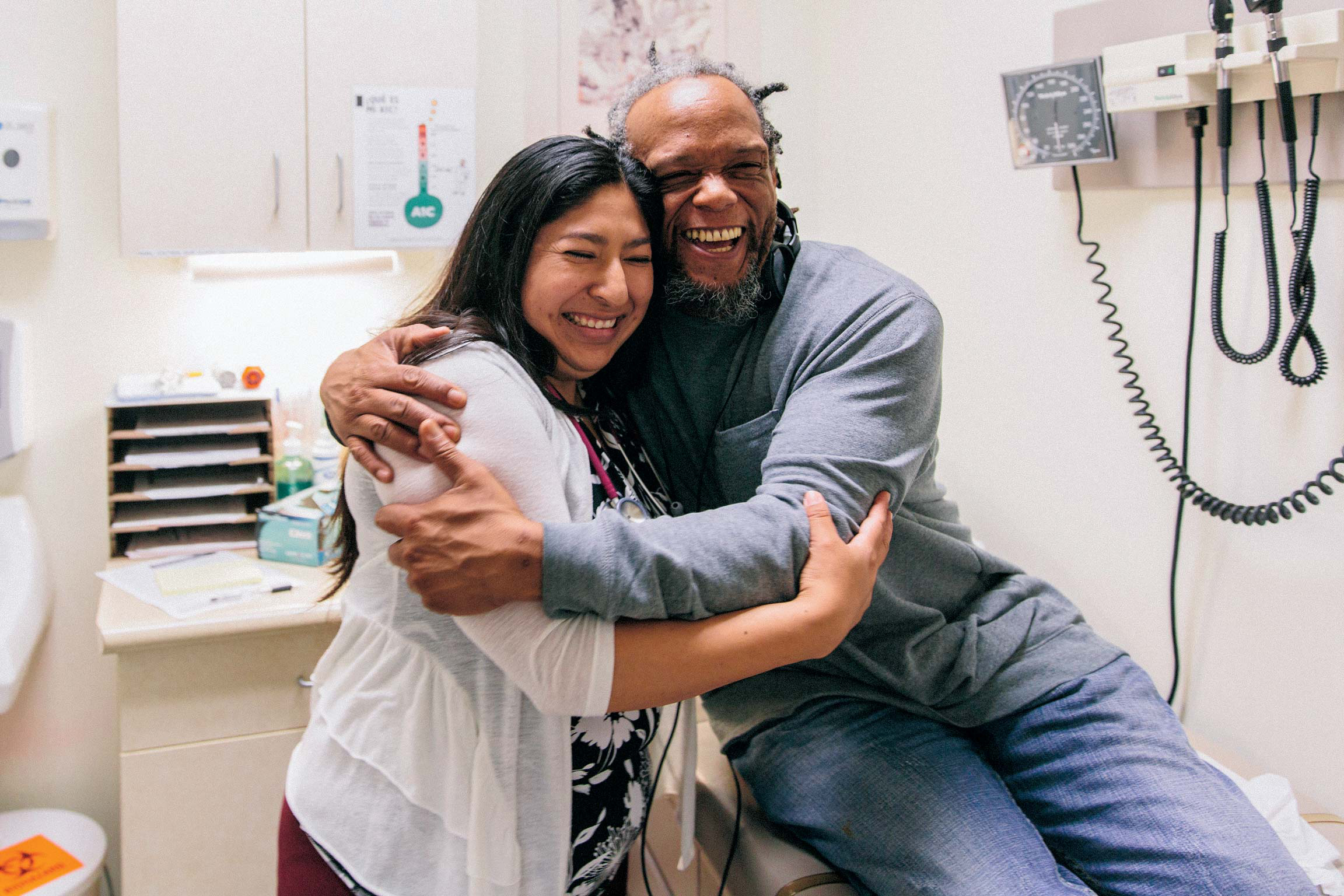

Sabin walked with the woman to the mammography department and scheduled an appointment for later that day. She waited outside the exam room during the 15-minute procedure and hugged the patient when it was over. She promised to let her know when the results came in.

A few days later Sabin delivered the good news: Negative.

Going out of her way to connect with patients was one of the most important skills she learned in USF’s Transition to Practice program, Sabin said. As a result, patients trust her, share intimate details of their lives with her, and reveal anxieties about their health.

“Conversing with patients, getting them to open up, inspiring them to stay engaged with their health, those are some of the skills I use every single day,” she said.

Transition to Practice (T2P), a four-month internship program that pairs recent nursing graduates with experienced nurse mentors at area clinics, gave Sabin an advantage in the job market, as well — which is how she ended up with a job offer even before her internship was over.

As Health Care Shifts, USF Leads

Sabin is one of 141 recent grads to benefit from T2P, a multi-year test program funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Kaiser Permanente.

The program has a 98 percent job placement rate and internship partnerships with 80 Bay Area clinics, schools, and hospices. And it’s just one of a handful of initiatives being piloted by the School of Nursing and Health Professions and its alumni. Each of the programs puts students and recent graduates on the front lines of compassionate care and provides bedside training in clinics and outpatient health centers.

That training is vital, because health care under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is undergoing a major shift — moving toward personal and preventative outpatient care and away from hospitals for non-emergencies. The change is meant to improve outcomes, cut costs, and reduce deaths from hospital-related errors and infections. The result? Nurses are needed in doctors’ offices and outpatient clinics now more than ever. Treatments that used to require hospital stays — like chemotherapy, blood transfusions, and many surgeries — can now be handled in facilities that discharge patients the same day.

While some nursing programs have been slow to adjust, USF has led the way, developing bedside nurse-training programs for outpatient care that have won support from regional and national funders, opened doors to jobs for graduates, and raised the standard of care for Bay Area residents.

The approach has been so successful that students in these programs average 250 clinical outpatient-training hours, nearly triple the 90 hours required in California.

“At USF, we continue to provide hospital-based nurse training, but we’ve also expanded the student learning experience to include senior care, home health care, and outpatient care — making them integral parts of our nursing and health curriculum,” said Associate Dean Scott Ziehm. “We incorporate community health care at many levels, not just in one class like many nursing schools.”

While gaining career training, students and alumni also serve communities from San Francisco to Oakland and from Marin to Sacramento, where they reach low-income families, the homeless, veterans, and other vulnerable populations — channeling the university’s Jesuit mission.

At Ward 86, Sabin learned to conduct psychiatric and physical assessments, discuss patients’ diagnoses with supervisors, and practice motivational interviewing to encourage patients to open up about their health and histories.

Her mentor, a 20-year nursing veteran, also helped her network for jobs. After completing T2P, Sabin started at Westside Community Services HIV clinic in San Francisco’s South of Market neighborhood, caring for HIV/AIDS patients. She later worked at California Pacific Medical Center, a San Francisco hospital, but felt something was missing.

“At the hospital I saw many patients come in again and again for the same conditions,” she said. “There wasn’t much time for education or prevention efforts.”

Today, Sabin’s back in a clinical outpatient setting, working as a registered nurse at Richmond Beach Primary Care clinic near Seattle. Outpatient care, it turns out, is her passion.

Oakland: Taking Time With Patients

At La Clinica De La Raza in Oakland, bilingual nursing students make sure patients — many of whom are low-income immigrants — receive the most from their doctors visits. About 12 USF graduate students a semester guide mostly Spanish-speaking patients through their appointments and spend extra time making sure they understand all the instructions and take their medications. It’s a crucial role since doctors spend just 15 minutes with each patient, in order to see as many as possible.

Many clients of La Clinica suffer from diabetes and hypertension, living examples of the epidemic of chronic illnesses that affect almost half of all Americans and comprise 86 percent of U.S. health care costs. By taking time to get to know her patients, master’s-level intern Daniela Vargas MSN ’16, MPH ’17 can help stabilize their blood sugar levels and decrease their hypertension — reducing the likelihood of a trip to the hospital where treatment is riskier and more expensive.

To educate them on the importance of regular checkups and prevention, she makes sure patients schedule their next appointments before they leave the clinic and asks them to show up, even if they feel fine when the date arrives.

“Before ACA, many of our patients were uninsured and didn’t regularly see a doctor. They waited until their diseases were so out of control they were forced to go to the hospital,” Vargas said. “Now, we work with them to prevent or manage their chronic diseases by creating individual action plans for each, and educating them on exercise, weight loss, and proper nutrition.”

Being part of La Clinica’s intern program is a dream come true for Vargas. She’s wanted to be a primary care nurse since working as a nursing assistant at a doctor’s office after high school. But when she looked into graduate nursing programs, few offered to train her in a primary care setting.

“I looked nationwide. I was willing to move anywhere. I couldn’t find anything, until USF,” Vargas said. “At La Clinica, we learn to talk to and connect with our patients. We have more one-on-one contact in a primary care setting than at a hospital, and we get to know the patients. I feel like the outcomes for them have been life-changing.”

Marin: Helping the Homeless

Just across the San Francisco Bay in Marin County, Rita Widergren ’66 is improving health care for another marginalized population — the homeless. Many of Widergren’s patients struggle with alcohol and drug abuse and suffer from chronic mental or physical health issues. They’re what nurses and doctors call “frequent fliers,” because they cycle in and out of hospitals, exhausting resources and bouncing from one crisis to the next — often as a result of running out of medication, injuring themselves, or passing out from an overdose.

Widergren, an award-winning public health nurse, has developed a solution to that revolving door. She calls it Opportunity Village Marin (OVM). It’s one of the few programs of its kind in the nation that accepts patients without requiring them to enter a detox program, a major deterrent for some patients.

Launched with support from Kaiser Permanente and Marin General Hospital, the nonprofit provides the county’s homeless with 21 days of free housing when they leave the hospital — a welcome respite of safety and stability. During that period, OVM’s tiny staff of Widergren and half a dozen volunteers — including several USF graduates, faculty, and students — connect them with doctors, social services, and long-term housing.

Since 2014, OVM has assisted 46 homeless patients, finding all of them a “medical home” where they receive ongoing care. None returned to the hospital in the 90 days after discharge, and 88 percent were placed in permanent housing — saving taxpayers and insurance ratepayers approximately $1.5 million by keeping them out of emergency rooms. Of the 12 patients with substance abuse issues, four voluntarily completed detox and now live in sober group homes designed to facilitate the transition to living on their own.

“OVM’s mission is to raise the voices of the most vulnerable and mobilize resources to stabilize their health,” Widergren said. “It’s the Jesuit Catholic tradition at work, supporting a culture of caring that respects and promotes the dignity of every person.”

Sacramento: Caring for Vets

Indeed, Jesuit values drive all the programs, said Margaret Baker, dean of the School of Nursing and Health Professions.

“These programs, in which our students work with some of our most vulnerable community members, promote care of the whole person,” Baker said. “These students truly learn what it means to be women and men for others.”

A good example is USF’s partnership with the Department of Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care that started a year ago to address a nursing shortage felt by another population with distinct needs — veterans.

USF’s VA partnership, a fast-track two-year program, places transfer undergraduate nursing students in veterans clinics and hospitals to learn how to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries, Agent Orange exposure, and other battle-related illnesses.

About 20 students are admitted to the program at USF’s Sacramento Campus each year, ensuring a small student-to-faculty ratio and personalized training from both USF and VA faculty. Students begin by conducting verbal health assessments and move on to more complex tasks such as starting IVs and shadowing VA nursing instructors around a variety of hospital units.

“One of the best parts of the program for me is the opportunity to work, train, and learn from VA nurses, doctors, and support staff,” said Matt Jones ’16.

Amy Phan ’16 said she was drawn to the program because veterans deserve the best care for serving our country. “This program is veteran-centered, which means we learn about the specific conditions and diseases that other nurses may not see in the general population. I think it’s important to be knowledgeable about these diseases and conditions, because if we don’t know how to treat them, we essentially aren’t giving veterans the best care we can,” she said.

Western Addition: USF’s Own Clinic

In the past six years, T2P, La Clinica, OVM, and the USF-VA partnerships have assisted hundreds and maybe thousands of vulnerable patients, as well as prepared a new generation of nurses for careers in an evolving industry, produced new evidence-based nursing practices, and built trusted community partnerships.

But that’s only scratching the surface, said Judy Karshmer, who was dean of the School of Nursing and Health Professions for the past 10 years until she stepped back from that role this summer and began a one-year sabbatical. Over her sabbatical, she’s leading a campus-wide effort to realize the boldest idea in the school’s history.

The school plans to establish a community health center and teaching clinic in San Francisco’s Western Addition, a neighborhood close to campus whose residents struggle with poverty, frequent emergency room visits for preventable diseases, and poor prenatal care and birth outcomes compared to the rest of the city.

The clinic, which will also treat university students, staff, and faculty, will be a one-stop shop for primary care and mental health needs. The University of San Francisco Integrated Health Clinic and Lab, as it’s being called, could also be a home for research on topics such as chronic disease management and environmental health — drawing on faculty experts from across campus in psychology and health informatics, Karshmer said.

She hopes to have the health center up and running by 2018.

“It’s the logical next step in the school’s effort to serve those most in need while also preparing the next generation of health professionals,” Karshmer said. “Ultimately, our goal is to close the health gap between the Western Addition and other parts of San Francisco.”