West Side Stories

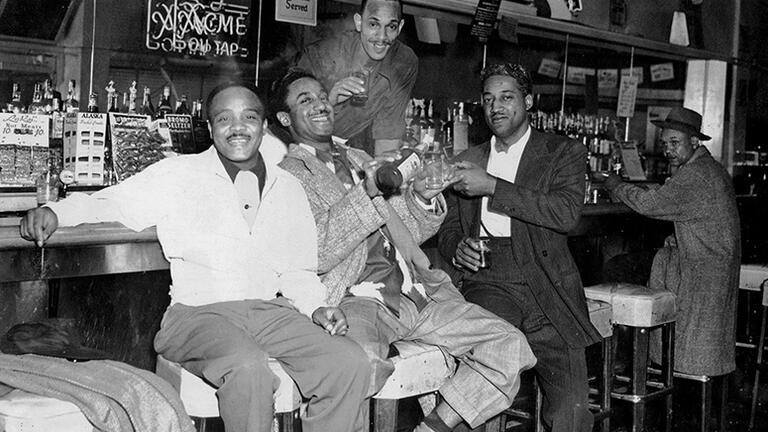

Seventy years ago, San Francisco’s Western Addition was known as the “Harlem of the West.” The neighborhood, just a few blocks from USF’s campus, had a thriving black culture and was famous for its jazz clubs like Bop City, frequented by musicians such as Miles Davis and Billie Holiday.

But then came urban renewal — a federally backed but city-led redevelopment project that remade streets; replaced Victorian homes with high-density affordable housing, public housing, and apartments; and created shopping centers, with the idea of boosting the economy and reducing “blight.”

Starting in the 1950s, homes and businesses were razed using eminent domain. Thousands of families were forced to outlying San Francisco neighborhoods or to Oakland, says USF Assistant Professor Rachel Brahinsky, director of the Master in Urban and Public Affairs program.

“We did all the bulldozing and thought that that would spur investment. And, in fact, for probably about a decade and a half, the land just lay fallow, because there wasn’t the kind of investment that folks anticipated would come,” said former San Francisco Redevelopment Agency head Fred Blackwell in a 2008 NPR interview.

The economic decline lingered for generations and contributed to a significant drop in San Francisco’s African American population, Brahinsky says. Today, only about 6 percent of San Francisco residents are black, census data shows, compared to 13 percent in 1970.

Urban renewal ‘decimated communities not just here in San Francisco, but throughout America.’

Many residents felt their neighborhood — also known as the Fillmore — was targeted for redevelopment because of racial bias. As one former resident told KQED in 1999, “The Fillmore did not feel blighted to me as a child. The only way that you can get to the issue of blight is to determine that the people who were living there, largely African Americans, had low incomes.”

Fast forward to the present and San Francisco supervisors seem to agree with that assessment. In September, they supported a resolution to rename Justin Herman Plaza — a prominent square on the city’s waterfront named for the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency director who spearheaded urban renewal.

Urban renewal “decimated communities not just here in San Francisco, but throughout America,” Supervisor Aaron Peskin told the San Francisco Chronicle after the vote.

Today, though the Western Addition is economically and racially diverse, the area has one of the highest percentages of residents living in federally subsidized housing, according to the San Francisco Housing Authority. And residents — particularly African Americans, who according to 2013 city data make up about 20 percent of the neighborhood — face disproportionately high rates of poverty, violence, and health disparities compared to the rest of the city, says the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Residents, nonprofits, and the city are working together to tackle those issues, including by partnering with USF on a number of initiatives. For decades, individual USF programs and professors have connected students to community groups that assist neighborhood residents and preserve the neighborhood’s history and culture. In 2014, the university launched Engage San Francisco, a program that formalized the relationship between USF and the Western Addition.

“Our role is to amplify and support the work Western Addition community members are already doing,” says Karin Cotterman, director of Engage San Francisco. “We don’t want to make the mistake of acting like ‘saviors’ — that would be presumptuous and ineffective. Instead, we’re fostering and facilitating ties between USFers and Western Addition residents, so more relationships can blossom.”

The university is involved in dozens of projects in the Western Addition, from teaching reading to assisting with job applications. Each benefits the community and USF students, with the students getting to put their classroom learning into practice.

“Our partners and community members help students understand both the strengths and challenges of the Western Addition,” Cotterman says. “Depending on their area of study, students may focus on how to improve policymaking, health disparities, education equity, the arts, social innovation, legal issues, and more.”

If these walls could speak

Western Addition resident Lynnette A. White worries that as San Francisco’s black population dwindles, the history of the black men and women who helped shape the city — like civil rights activist Lulann McGriff or longtime Superior Court Judge John Dearman — will also disappear.

“I strongly believe that everyone should know about everybody’s contribution in this city,” says White, who’s lived in the city for nearly 50 years and, alongside other activists, fought urban renewal. “It’s very important. White people are not the only people who’ve made contributions to San Francisco.”

That’s why White and her friend Altheda Carrie teamed up with USF students and professors in the Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars and Martín-Baró Scholars programs to preserve the stories of local black leaders. Students in these programs, which emphasize diversity and service learning, are researching and writing biographies of nearly 100 black leaders for a book to be published in fall 2018. The leaders are depicted in a mural, called “Inspiration,” that’s spread across five walls outside the Western Addition’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center.

Actor Danny Glover and former Mayor Willie Brown are on the wall, as is Carrie, a former teacher. White’s husband Eugene A. White, an artist, is there, and so are attorneys, principals, firefighters, and other community role models.

To gather information for the multi-year project, students are digging through archived newspaper clippings, interviewing family members and friends, and in some cases interviewing the subjects themselves.

“Learning about the different African American men and women who have done something for San Francisco is refreshing, because many students don’t know about it,” said Chaniece Jefferson ’19, who participated in the project last year.

Jefferson wrote about William Cobb, the first black principal in the San Francisco school district, and Joseph Marshall ’68, a USF graduate and MacArthur “Genius Grant” winner, who started an after-school program that combats gang violence and provides college scholarships.

‘What I learned today’

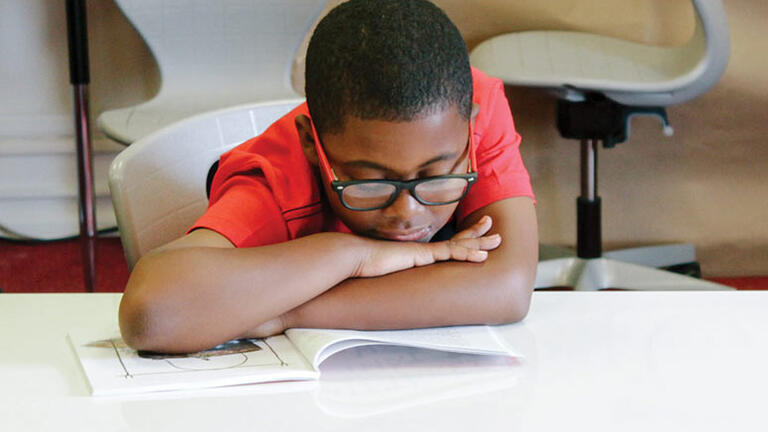

For most kids, summer vacation means goofing off and catching up on cartoons and video games. But taking a long academic break can set back kids’ reading development, causing cumulative damage over the years. It’s an issue that disproportionately affects children in under-resourced communities, who often have less access to summer enrichment opportunities.

Shamica Simpson’s kids, though, have no trouble with reading loss. Marlon, 11, and Jaden, 9, are enrolled in a summer reading program taught by USF graduate education students.

“When my kids go back to school, they’re not behind, they’re ahead,” says Simpson.

The program, co-directed by USF education Professor Helen Maniates and nonprofit Collective Impact Executive Director E’Rika Chambers, is a 10-year-old collaboration with the Schools of the Sacred Heart. Each summer, 10 to 20 USF teaching students work with approximately 175 elementary and middle school students in small classes. The USFers, all credentialed California teachers, earn class credit for teaching.

Simpson says the program has been a game changer for Marlon. When he was younger, Marlon's kindergarten teacher told Simpson that he needed extra help to catch up with his peers. Because reading didn’t come naturally, he thought of it as a chore and resisted learning. After entering the summer reading program three summers ago his attitude changed.

“It’s like, ‘Oh mama, this is what I learned today!’ and, ‘Mama, did you know this?’” says Simpson.

Now Marlon is an honors student. And Jayden, also a top achiever, won second place in a spelling bee. Simpson’s daughter Nevaeh, 4, likes to get in on the action too when her brothers read books, like one about Jackie Robinson.

Telling their own stories

When Nicola McClung, an assistant professor of learning and instruction at USF, began reading to her infant daughter, Oona, she wanted her to see and hear stories about people with different racial backgrounds, with same-sex parents, and with nontraditional gender identities — families similar to her own. But McClung couldn’t find any.

“How do you explain to a 2-year-old that a single-parent family is a complete family when all the books she reads or hears read to her are about dual-parent, hetero families. And white and able-bodied?” McClung asks.

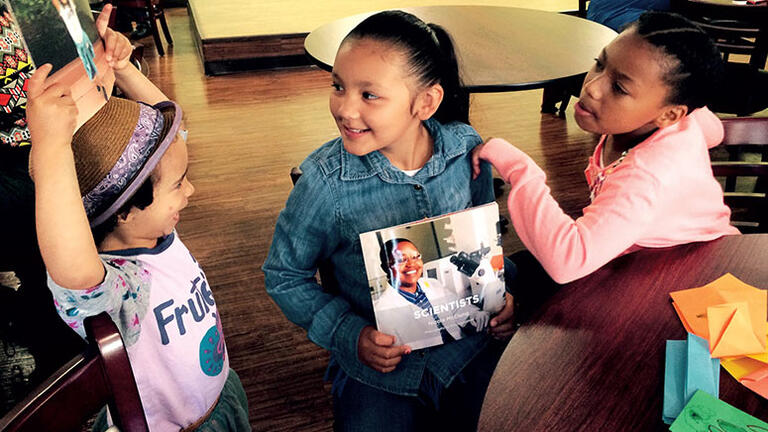

For McClung, exposing Oona — whose ethnic background is half European American and half East African — to stories about such families illustrates America’s diversity and highlights how her own family is part of the nation’s tapestry. Rather than throw up her hands, McClung co-founded the award-winning nonprofit Xóchitl Justice Press with adjunct education professor Arturo Cortéz. Their mission? Publish books written by children from diverse backgrounds that showcase people and characters from a variety of ethnicities and households.

Since 2014, the press has published 57 books, including such titles as Getting Stronger When Our Park is Cleaner, How to Ride the Bus, and Friendship. The books are written by elementary school students in the Western Addition’s Prince Hall Computer Learning Center’s summer program, and by middle schoolers at Sacred Heart in Atherton, California, where one of McClung’s former doctoral students introduced the program.

Eleven-year-old Western Addition resident Jordan Pickett is author of the book Giving the Homeless a Hand. Last year he and three friends helped organize a fundraiser to buy and distribute food and clothes to homeless men and women in their neighborhood. Then the students wrote about the experience.

Jordan brought his book to show his classmates at Cobb Elementary School.

“One kid asked me, ‘How does it feel to write a book?’” Jordan says. “I said, ‘It feels great.’”

After the shooting

Demetria Gigante can’t remember much about the day bullets flew into a car she was in and struck and killed her two friends. Her mind has blocked out the details. But now — about a decade later — when there’s violence in her Western Addition housing project, Plaza East, her post-traumatic stress disorder is triggered.

“I relive my trauma every time there’s a shooting,” Gigante says.

Unfortunately, that trauma is sparked far too often — and the 44-year-old has had trouble holding down a steady job.

But Gigante is trying to return to normal life, meeting with a mental health counselor to deal with her pain, and hunting for work. She met USFer Jacqueline Brown MPH ’17 at Plaza East, where Brown set up shop for 52 weeks last year to provide job and career advice to neighborhood residents.

As an AmeriCorps volunteer with Engage San Francisco and the workforce training nonprofit The Success Center, Brown helped dozens of Western Addition residents connect to education and housing resources and search for and apply to jobs. (AmeriCorps is a domestic service program, similar to the Peace Corps.)

She showed Gigante how to update her resume, write more effective cover letters, and use her cell phone to find jobs, since she doesn’t have a computer.

“I really appreciated her,” Gigante says of Brown.

From homeless and shy to center stage

For Judith Cohen, founder and executive director of performing arts nonprofit Handful Players, children’s theater is more than a training ground for budding actors.

“Children in the Western Addition are exposed to a high degree of violence, bullying, drug abuse, incarceration, and homelessness among their family and neighborhood,” says Cohen. Through performing arts education, Handful Players teaches cooperation, listening, focus, and other life skills; builds students’ confidence; and nurtures their potential.

Handful Players operates after-school performing arts programs in Western Addition schools for students ages 8 to 18 — students like “E,” a shy 10-year-old, who was homeless when he first enrolled. Handful Players was a source of stability and consistency for the boy, who slowly gained confidence and landed a lead role in a play.

That kind of transformative work is what drew Taylor Louise Garry ’13, MA ’14, a performing arts and social justice (PASJ) major in the dual degree in teacher preparation program, to volunteer with the nonprofit in 2013. Handful Players allowed her to be both an artist and an activist, which is the focus of PASJ, Garry says.

It’s incredible that my senior project became something that’s allowed USFers beyond me to work in the community and make a difference for so many children.

For their PASJ senior project, Garry and Cecilia Rehm ’13 filmed a documentary about Handful Players and led weekly student rehearsals at John Muir Elementary School.

The USF pair’s outreach to Handful Players sparked a lasting partnership. Now USFers regularly intern with Handful Players, traveling to Western Addition schools to not only teach students the fundamentals of theater, but to also have larger conversations about issues like bullying, inequality, and injustice.

“It’s incredible that my senior project became something that’s allowed USFers beyond me to work in the community and make a difference for so many children,” says Garry, who is now a fifth grade teacher at San Francisco’s Presidio Hill School. “My experience with Handful Players cemented my decision to become a teacher.”