A USF Grad Behind Team USA’s Athlete Experience

Rocky Harris ’02 is the Chief of Sport & Athlete Services at the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC), overseeing the work that “interacts with the athlete and supports the athlete,” including NGB services, athlete services, high performance, Olympic and Paralympic operations, sports medicine, training centers, and more.

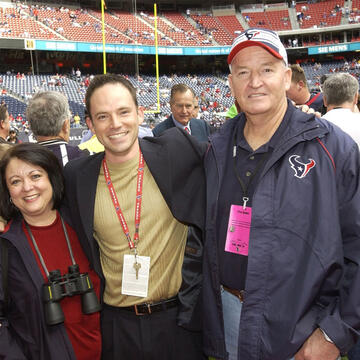

Before the USOPC, he was CEO of USA Triathlon, served as COO at Arizona State athletics, and led major growth initiatives with the Houston Dynamo after earlier stops with the Houston Texans and San Francisco 49ers.

From a Coach’s Kid to Sports Business

Rocky grew up with sports baked into daily life. “My dad was a high school coach,” he told us. His mom worked in media, “the art director for the Arizona Republic,” which gave him early exposure to how stories shape perception. At Arizona State, Rocky knew he wanted a career in sports, but the path was not obvious. “Back then they didn’t have sport management programs,” he said. So he started where he could: working for ASU athletics, and at a youth sports nonprofit that ran programs like “the Fiesta Bowl youth sports camps.”

His dad gave him a key nudge. Rocky was thinking about coaching, but his dad pushed him toward the business side: “In the sports business, I see that growing dramatically over the next decade… when the businesses grow, they have to hire more people.” Rocky took the advice, even though he admitted, “I didn’t really know what that meant quite frankly.”

Letters & Persistence

Rocky’s first big break in pro sports came from relentless outreach and one very human habit: showing up early. He chose the University of San Francisco, Master’s in Sport Management for grad school because he could work full-time and wanted to be “in a vibrant sports market.” Then he started contacting anyone connected to San Francisco. “Back then we wrote letters… there were not emails that you sent out,” Rocky said. He wrote to Tom Rathman, a 49ers coach he met through a football camp, and began sending the 49ers PR director, Kirk Reynolds, letters “maybe every couple weeks.”

The moment it clicked is straight out of a movie, except it was also brutal. Rocky was moving with “no money,” wrecked his condo carport, and the damage “cost me $900, which was all my money I had.” Then, on the drive to San Francisco, the phone rang. “It was Kirk Reynolds… ‘I’ve gotten your letters. I’ve heard from Tom… I have a game day internship for you.”

Rocky earned that chance, then kept earning the next one. He became a training camp intern, then a season intern, then got hired full-time while finishing grad school. “I made it in there… but I worked hard,” he said.

Career Changing Wins

One of Rocky’s defining early stories is about how trust gets built in the unglamorous moments. With the 49ers, he was often assigned to “low-level athletes,” but when Terrell Owens was suspended and refused to talk to the media, someone finally asked Rocky to try. Rocky walked up and kept it simple: “My job is to get you to speak to the media, and your job is to catch touchdowns… by not speaking to the media… I’m not able to do my job.” He added: “I want to set you up so you can at least say the right things, get in and out of there as quickly as possible.”

Owens’ response stuck with him: “You’re the first person who was honest with me about your intentions.” That moment built Rocky’s reputation as “someone who could work really well with athletes,” and it led to a major leap, joining the Texans PR team and becoming, “the youngest PR director in NFL… history,” as he was told at the time.

USF: applied learning, instant network, real jobs

Rocky credits the University of San Francisco Sport Management program as a true accelerator at a critical point in his career. What separated it from other programs was how applied the learning felt. “Most of the professors were in industry working the jobs,” he said, which meant classes were rooted in real scenarios, not just theory. He consistently found himself pulling lessons from USF and applying them directly in his early roles.

The cohort structure also played a major role. “We were a cohort… going through it together,” Rocky explained, creating a sense of shared experience and accountability. That model helped form an instant network of peers who understood the industry and remained valuable connections long after graduation. Most importantly, the program was built around outcomes. “It wasn’t just preparing us to graduate,” Rocky said. “It was preparing us to get jobs.”

When Rocky talks about what separates strong operators, he goes beyond hustle. He looks for people with “the ability to solve problems that seem unsolvable,” who can see beyond their department and “look across an entity and see how things connect.” Hard work matters, but so does ownership, intelligence, and creativity, especially when the work is ambiguous.

His own career operating system is clear:

- Your job is to get really good at the job you were hired to do.

- What are the problems that keep your boss up at night and how can you offload them?

- What problem is the organization trying to solve?

His advice is blunt: if you skip step one, “they lose credibility because if you’re not even good at your job, why are you trying to tell me how to do mine?”

Using Sport to Benefit Society

Rocky’s motivation has evolved from teams and wins toward something bigger: “utilizing sport to benefit society.” He pointed to the first NFL game in New York City after 9/11, when he was part of the 49ers advance team. The security briefing included “FBI, CIA, everybody,” and in the stadium he sat next to a fire chief who had lost nearly his entire squad. For Rocky, that game showed how sport can rally a city when it needs something shared.

He recalled another moment as Texans PR Director after Hurricane Katrina, when displaced families arrived in the area around the Astrodome. In a meeting about game ops, he challenged an idea to build fencing that would separate evacuees from fans: “You’re going to fence people off from our fans? That's going to look like we’re jailing them.” Instead, he pushed for bringing people together, and he remembers it becoming “an awesome event where Texans fans opened up their tailgates to evacuees.” That throughline has carried into his leadership today: “How do you use sport to be a positive force in society.”

Learn more about USF's MS in Sport Management program, and visit Sports Business Ventures (SBV) for more content like this.